7 min read

What is Wellness Design?

How to apply the principles of Wellness Design to the Healthy Home.

9 min read

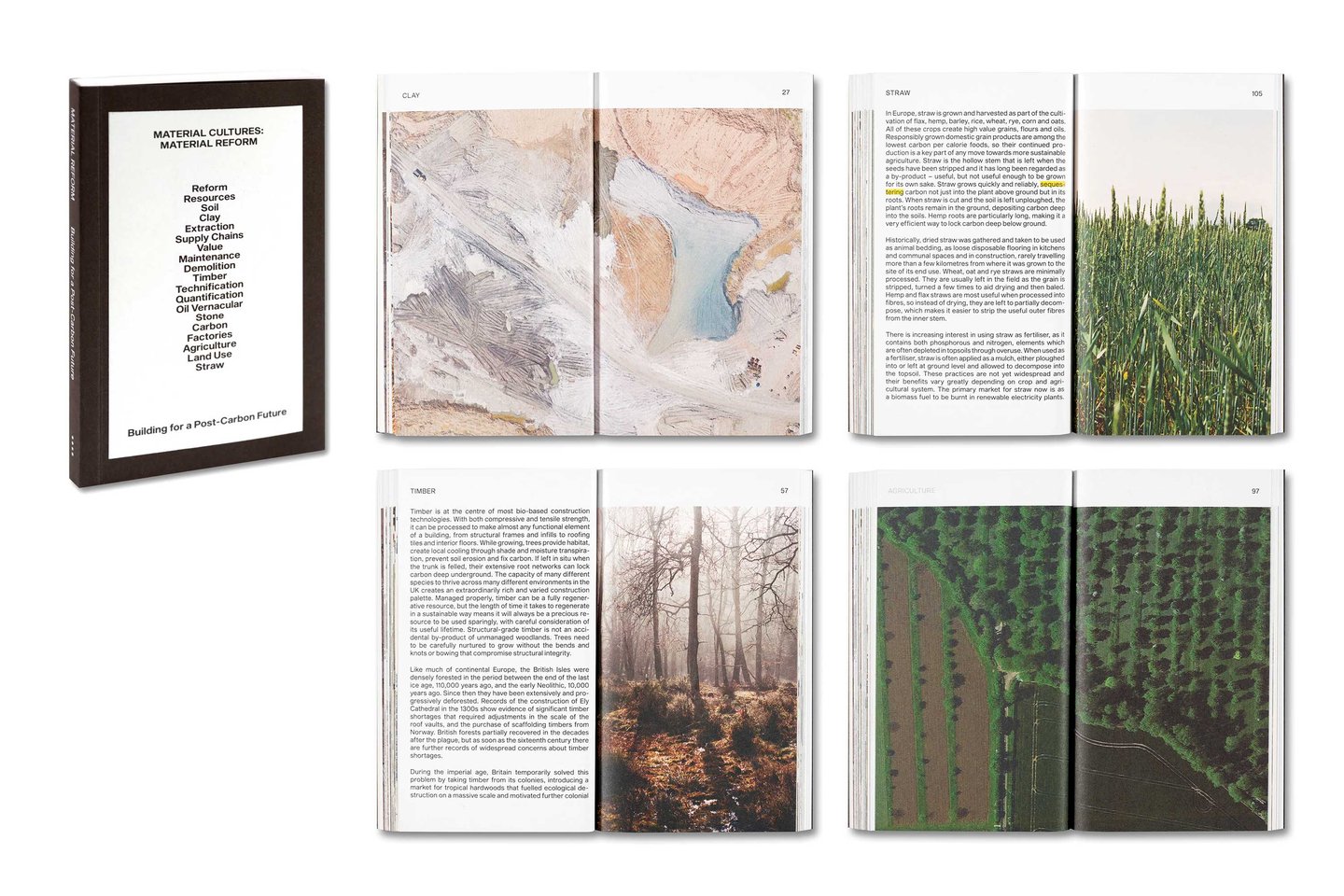

Founding director Paloma Gormley sits down with WLLW to discuss the potential of bio-based materials, and how we can make meaningful progress towards a post-carbon built environment.

As a practice, we examine the role material and industrial cultures play in creating the buildings in which we inhabit. We look at how materials and industry play a part at every level, from how buildings are made, how they function, how they feel, and what they cost – which can be seen in broad terms, including the human cost, the environmental cost and the cost to health. The idea is to challenge these systems, the technology, supply chains and regulations and the materials that make up the construction industry. We want a building industry that is for the better.

In a way, the materials that you just mentioned are the four pillars of low-carbon construction. They are so much better for the environment and our health. What you end up with when using these materials is a relatively reduced palate, but it is also surprising just how many permutations each have. The book focuses on these materials and in some cases how they’ve been used in industry to date.

“As a practice, we advocate for bio-based materials in construction – they’re better for the environment, better for biodiversity and better for our health.”

Paloma Gormley

Timber is a prolific example. Dating back to the 20th century, forestry has become so highly industrialized via the plantation forests. These were designed to be efficient for timber construction, but they have ecological drawbacks – the lack of biodiversity they support and the lack of resilience to disease for instance. The book addresses other forms of forestry that we could use, and highlights what effect this would have on the type of timbers available on the market. As a practice, we advocate for bio-based materials in construction – they’re better for the environment, better for biodiversity and better for our health. Yet we’re not using them, and when we are, like the timber example, it’s not done well.

The way we build now is incredibly carbon-intense because construction culture is based around concrete and steel, and then typically supplemented with petrochemical-based insulation materials. We've been able to afford to do that for the past 100 years because we haven't counted the real cost of that carbon. If we did, we’d realise that we have done a huge amount of damage. We need to radically change the way that we build in order to not only address the amount of carbon but also move towards buildings that do more good than harm.

When plants grow, they sequester carbon and when you take the material from those plants, you can lock up that carbon and store it in a building. Buildings are great places to store carbon because (if done well), they stick around for a long time. The more carbon we can have locked away, the better. These bio-based materials are also not sending out harmful toxins into the interior environment of our buildings, meaning there are better health outcomes for occupants.

It’s interesting because there has been a huge amount of work in the name of sustainability over the last 20 or 30 years. But the focus has been on technological solutions to reduce carbon, such as reducing heating and cooling demands. While that is reasonably effective, it is only looking at half the story, and the systems and technology that are introduced are themselves high carbon in their manufacture and production. Part of the problem is we are swept up in a culture of designing and producing our way out of problems. We try to outsmart the world with more tech. It is an interesting question for me, to try to understand the psychology of that. Is it necessary? Are many of the answers not already there?

Architecture and construction is inherently slow to adapt. Medium to large projects work at the timescale of one to 10 years from inception to completion, so there’s a lag. There is a huge amount of infrastructure and systemic change required, and then there’s the knowledge and skills on-site, which are currently structured around the conventional way of doing things. Manufacturing and the production of the materials need to change. Then there is testing and regulation, which is ultimately a financial barrier because it costs a lot to put these materials through testing processes.

When you are talking about plant-based materials, you must remember that they come from industries with less money than, say, the oil industry. Usually, it is farming, and that, of course, has been underfunded and undervalued for a long time.

There are a lot of externalities to the current way of doing things that are not accounted for, be that the carbon costs or the costs on people's bodies or the cost to our health and our ecosystems. So many of the materials that we rely on today are very cheap from a financial point of view, but they have a disastrous social and ecological impact. Generally, we live in a world of global supply chains that are out of sight, and the way we use material in construction, well, that’s very different to the context in which it is being extracted. Because these processes are happening so far away, we are removed from that. We’ve lost sight of the environmental and social cost of their production and extraction.

So, the processes of extraction and processing of materials are often dangerous to health – poor air quality and extremes of heat in mines being one example. That’s to say, it puts people’s bodies at risk. There’s very little acknowledgement of that, and it’s not accounted for in the price of the goods. Externalising labour is very common. It is often happening in the global south, which perpetuates that colonial relationship in these supply chains.

Our approach is very much about starting with a landscape and mapping its ecological territory. At our practice, we consider the land, asking what it would need and how it might flourish. Depending on the land, that could be the reintroduction of water and beginning the process of renewal, which will lead to saturation of the ground and the proliferation of plant species. And then we can begin to think about what sort of building materials might work here. It’s a bit like going back in time to when we understood how things were made, where they came from, and the production and extraction were local and far more hands-on. Things didn’t move far then, and that’s the approach we advocate, that return to the local. It is about building up very particular, nuanced knowledge between those who make and those who grow. Again, it is a return in time in many ways.

The Flat House was a prototype building that could be grown on a farm. Basically, we took two parts of the hemp plant and made an insulated house with one part and with the other, we made the cladding. The building is modular and was built very quickly, efficiently and cheaply. It was mostly made of materials from the farm, and it sequesters more carbon than it used in its construction. We wanted to demonstrate the possibilities of bio-material-based construction. We are currently working on a housing project – quite a large one, seventy units across four blocks, and it’ll be based on the same principles. We are working with farmers to develop supply chains and foresters to supply materials, and it is a very low-carbon process. It’s got a fair way to go, probably another two or three years away.

It seems there is a growing interest globally and an awareness of these issues, but it's not yet mainstream by any means. People are coming to this from different areas. One is health, because there is a growing awareness that a lot of the materials that we have been casually putting into our homes for a long time are toxic and contributing to really dangerous levels of interior air pollution. Sometimes the air inside is worse than the air outside, and that’s got a lot to do with the glues used in household furnishings, chipboards, carpet, laminates, so on. Usually, lower-cost materials are more toxic, so there’s an injustice in that sense, socio-economically speaking.

“There is a growing awareness that a lot of the materials that we have been casually putting into our homes for a long time are toxic and contributing to really dangerous levels of interior air pollution.”

Paloma Gormley

Another thing is that people are gravitating towards more natural items, be that in beauty products or in architecture and design. There is a desire to return to a sense of closeness to nature. You see that in the rising popularity of off-grid, timber holiday Airbnb’s and homes. Finally, there’s the growing awareness around sustainability too, and a collective sense that we need to shake up the status quo in multiple industries, when it comes to our homes.

Yes absolutely. Any kind of retrofit or renovation is an opportunity. It all comes down to the materials that you specify. It could be just selecting wood fibre insulation, over mainstream synthetic or petrochemical options, for instance. Because that is a product that will lock up carbon without any of the harmful side effects. In the kitchen, either choose not to refurbish (not ripping things out is one of the best things you can do) or make sure the materials are as natural as possible. That could be unprocessed stone from a local quarry or using reclaimed materials wherever possible.

Full-scale, systemic change has to happen. And it will likely happen from the top. Just taxing carbon would be a very simple, universal reset in terms of how we calculate the value of things. We could also incentivize and invest in material innovation and testing in order to change product manufacturing. The sad thing is that right now, there is a huge amount of work out there in terms of product manufacturing that is not able to break through into a commercial market and become available because there are so many barriers. So, it is about removing those and championing a whole-scale rethink.

Photography: Material Cultures, Oskar Proctor, Mack Books

Further Info

For more on Material Cultures' work, visit their site here

A fascinating Podcast interview by Grant Gibson with Material Matters co-director, Summer Islam

Bjørn Berge, The Ecology Of Building Materials (Taylor & Francis, 2012)

James Woudhuysen, Why Is Construction So Backwards? (Wiley, 2013)

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs The Climate (Simon & Schuster, 2019)

7 min read

How to apply the principles of Wellness Design to the Healthy Home.

2 min read

It is my mission to connect our readers with a global network of experts, designers and makers.